I tried to mentally erase the T-shirts and selfie sticks and resurrect the fallen columns. Vespasian and Titus, riding chariots, would have been two dabs of purple surging up the ramparts of the Capitoline through a sea of white togas. In their train, thousands of Jewish slaves shuffled with bowed heads while the heaps of plundered gold and silver bobbed above them, winking in the sun. “Last of all the spoils,” writes Josephus, “was carried a copy of the Jewish Law” — the Torah.

Josephus reveals exactly where these spoils ended up. Vespasian had a new temple — the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace) — built adjacent to the Forum where “he laid up the vessels of gold from the temple of the Jews, on which he prided himself; but their Law and the purple hangings of the sanctuary he ordered to be deposited and kept in the palace.” The palace, in ancient Rome, meant the Palatine (the word palace derives from the hill’s name) — and so, as the autumn sunlight brightened from silver to gold, I mounted the imperial summit.

After the buzzing, marble-strewn congestion of the Forum, the Palatine is like a country stroll. The huge squares of weedy grass and clumps of umbrella pines outlined in brick stubs could almost be farm fields — but, in fact, most of the stubs are remains of a colossal royal residence, the Domus Flavia, inaugurated by Vespasian and completed by his wicked, wildly ambitious second son, Domitian. Josephus, whose life spanned all three Flavian emperors, would have come to the Domus Flavia to pay homage to his patrons and perhaps murmur a prayer before the sacred scroll they had cached here.

Credit

Susan Wright for The New York Times

I lingered on the Palatine for half an hour, trying to conjure the nerve center of an empire from its ruins. Somewhere buried under the dandelions and broken shards stood an inlaid niche or marble alcove where the stolen Torah was caged like a captive king.

Josephus’ footsteps lie closer to the surface in the Templum Pacis. I’d never heard of this monument, though I must have passed its ruins a score of times on the wide glaring Via dei Fori Imperiali (Street of the Imperial Fora) that Mussolini carved out as his own triumphal route between the Colosseum and Piazza Venezia. On my second morning in Rome, Josephus’s text in hand, I stood by the railing near the Forum ticket booth and peered down at the ongoing excavations of the temple’s sanctuary, arcades, fountains and gardens. Josephus notes that the Templum Pacis, built “very speedily in a style surpassing all human conception,” housed not only the spoils of Jerusalem, but “ancient masterpieces of painting and sculpture … objects for the sight of which men had once wandered over the whole world.”

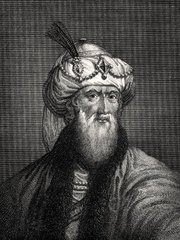

Credit

Culture Club/Getty Images

These masterpieces have long since vanished, but a wall of the temple still stands at the entrance of the sixth-century Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damiano, now a Franciscan convent. One of the resident brothers, who humbly insisted on anonymity, showed me around. “The Templum Pacis was not only a shrine but a kind of cultural center,” he said. “We’re standing on the site of the temple’s library where the Forma Urbis — an immense marble map of the city — was displayed.” He pointed out a rusty bent spike that once fixed marble veneer to the rough-hewed stone. “Go ahead and touch — it’s been here since the first century A.D.”

I was itching to get down to the crypt, which covers part of the footprint of the Templum Pacis, but first we ducked into the basilica and took a moment to savor its principal artistic treasure: a shimmering 6th-century apse mosaic of Christ surfing roseate clouds flanked by saints. Perhaps I’ve read too many thrillers, but as I gazed up at this solemnly joyous creation, I imagined a plumb line dropping from the tiles of Christ’s outstretched hand and coming to rest, magically, on the exact spot where the menorah had been stashed — fanciful, but not impossible.

Credit

Susan Wright for The New York Times

The sacred loot has disappeared without a trace, but a shelf of thrillers could be spun from the theories, myths, sightings and urban legends about where it supposedly ended up: hidden in a cave, glittering on the altar of the Basilica of St. John Lateran, carted off to Constantinople, tossed in the Tiber, and, most recently, squirreled away in a sub-subbasement of the Vatican. Alessandro Viscogliosi, a professor of the history of architecture at the University of Rome whom I met toward the end of my stay, has a more plausible — though mundane — explanation: When the Templum Pacis burned in 191 A.D., the gold and silver vessels melted and were subsequently salvaged and recast, probably as coins.

“No one really knows what happened to the stuff,” said Steven Fine, a professor of Jewish history at Yeshiva University in New York and the director of the Arch of Titus Project. “There’s a common desire to establish continuity through things — and certainly the visual environment of Rome fosters this.”

Be the first to comment