BERLIN — The Nazi guard lived a quiet life in New York City for decades, having lied on his United States immigration papers in 1949 about the type of work he did during World War II. But on Tuesday, he was deported to Germany, ending a 14-year battle to remove him from American soil.

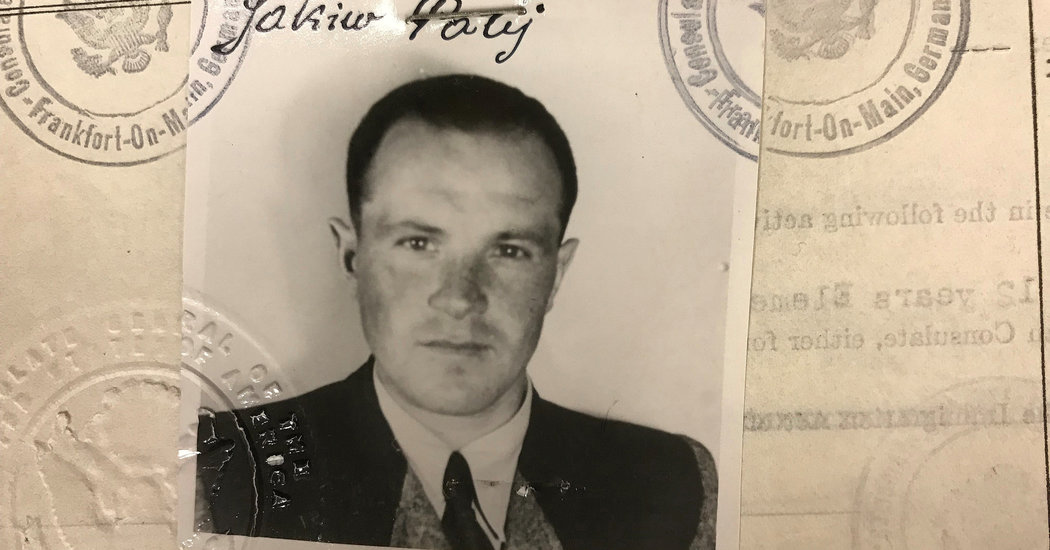

The former guard, Jakiw Palij, is believed to have been the last surviving Nazi war crimes suspect living in the United States. First tracked down by investigators in 1993, Mr. Palij was stripped of his American citizenship 10 years later when a federal judge found that he had falsely claimed in his visa application that he had worked on his father’s farm in Poland and at a German factory during the period when he was actually serving the Nazis.

In 2004, a federal immigration judge ordered that Mr. Palij be deported. But for years, no country would accept him.

Germany had long refused to do so because Mr. Palij, whose birthplace was once in Poland and is now part of Ukraine, is not actually German. Poland and Ukraine refused to take him, saying he was Germany’s responsibility. On Tuesday, the German foreign minister, Heiko Maas, acknowledged as much.

“We accept the moral obligation of Germany, in whose name terrible injustice was committed under the Nazis,” Mr. Maas told the newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. “We are taking responsibility vis-à-vis the victims of National Socialism and our international partners — even if that demands of us what are at times politically difficult considerations.”

Mr. Palij, now 95 and frail, arrived at Düsseldorf Airport early Tuesday and was taken by a Red Cross ambulance to a nursing home near Münster, in northwestern Germany. Until Monday, he had been living in a two-story red-brick house in Queens. Jewish activists had frequently staged protests outside the home.

American officials and diplomats had long urged Germany to take in Mr. Palij, but the efforts appear to have intensified under President Trump. The American leader regularly raised the issue in meetings with Chancellor Angela Merkel, officials said, and the new ambassador to Berlin, Richard Grenell, made it a priority in recent weeks.

“To protect the promise of freedom for Holocaust survivors and their families, President Trump prioritized the removal of Palij,” the White House said in a statement on Tuesday.

Like other young men from Poland and Ukraine during the German occupation, Mr. Palij was trained by the Nazi special police, the SS, as an 18-year-old. He is believed to have served as an armed guard at the Trawniki labor camp in 1943. On one day that year, more than 6,000 Jewish men, women and children died in the camp.

Mr. Palij has long denied participating in any killings, saying that he had merely guarded bridges and rivers. The SS forced him to work for them, he said, threatening to kill him and his family. “I know what they say,” he told The New York Times in an interview in 2003, “but I was never a collaborator.”

But the United States government determined in the early 2000s that he had participated in the persecution of Jews at Trawniki.

Around the residential block in Queens where Mr. Palij had lived since fleeing Germany, opinions about his deportation diverged sharply.

Maria Rososado, 70, who lives across the street, said she would often see Mr. Palij outside, cleaning his front yard and sidewalk. He mostly kept to himself, she said.

In the brief conversations she had with her neighbor, he was visibly sick, she said, and did not appear to have many years left. “He was just an old man,” she said. “He was not a bad person. He was a good neighbor.”

Adam DiFilippo, 33, whose stepmother is of Jewish descent, took a different view.

“This man deserves what he gets,” Mr. DiFilippo said. He said he learned of Mr. Palij’s past when students from a Jewish high school in Lawrence, N.Y., protested outside his home last November.

“This is New York City. We all have the freedom to be whatever we want,” he said, adding, “Just because you’re a New Yorker doesn’t give you the right to be a Nazi.”

Since 2005, the Justice Department has won deportation orders for 11 Nazi criminals, but only one of them has been successfully sent abroad: John Demjanjuk, a retired autoworker who had also served as a guard at Trawniki. He died in Germany in 2012, at the age of 91, before he could serve out his jail sentence for his role in the death of 28,000 people.

The remaining nine people subjected to deportation orders all died in the United States before facing justice. In the words of a Justice Department official, Mr. Palij is the “last adjudicated Nazi criminal in the United States.”

John Surico contributed reporting from New York.