The “La Croixs Over Boys” T-shirt line boasts nearly 3,500 Instagram followers.

Rapper Big Dipper’s comical R&B-inspired single “LaCroix Boi” has racked up more than 538,000 YouTube views since being released last summer.

The hashtag #LaCroix has been used more than 187,000 times.

Flavored sparkling water brand LaCroix has become a social media darling and propelled itself into mainstream pop culture in a relatively short time. The trendy seltzer in colorful cans has also seen major sales growth and helped boost the entire sparkling water market.

National Beverage Corp., owner of LaCroix, reported net sales of $826.9 million for its 2017 fiscal year, up from $662 million in 2013 and $575.1 million in 2009, according to the company’s annual reports. While the entire sparkling water category saw a 16.2 percent increase from 2015-2016, LaCroix alone grew 72.7 percent.

But how exactly is LaCroix creating such growth? What makes it different from other sparkling waters out there?

It’s older than most millennials, but it’s marketed in the most millennial way possible.

While it may seem like an overnight success to some, LaCroix has actually been around since the 1980s as a regional brand available only in the Midwest.

Beverage industry experts attribute its mainstream success to the company being in the right place at the right time to tap into several millennial-driven market trends, including their desire to reduce their sugar intake and habit of instagramming their favorite products.

LaCroix took to social media to help drive its fame, partly out of necessity, since marketing a brand can be expensive. LaCroix rarely grants media interviews and did not respond to interview requests from HuffPost, so we talked to Duane Stanford, executive editor at Beverage-Digest, for some background.

“Some of the social media happened because the consumers that were drinking LaCroix did what they do with a lot of things ― they shared it and talked about it,” Stanford said. “It has enough of an interesting package and fun, interesting names like ‘pamplemousse’ for the grapefruit-flavored sparkling water that it kind of almost created a life of its own online, and the marketing teams at LaCroix were very smart in capitalizing on that as well, probably even beyond what they had expected.”

While seltzer consumption remains small compared to traditional soda brands ― it makes up about 1 percent of beverage occasions, according to David Portalatin, vice president and food industry adviser at market trends firm The NPD Group ― industry experts say major soft drink companies, like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, are taking notice of LaCroix’s success and beefing up their own sparkling water offerings.

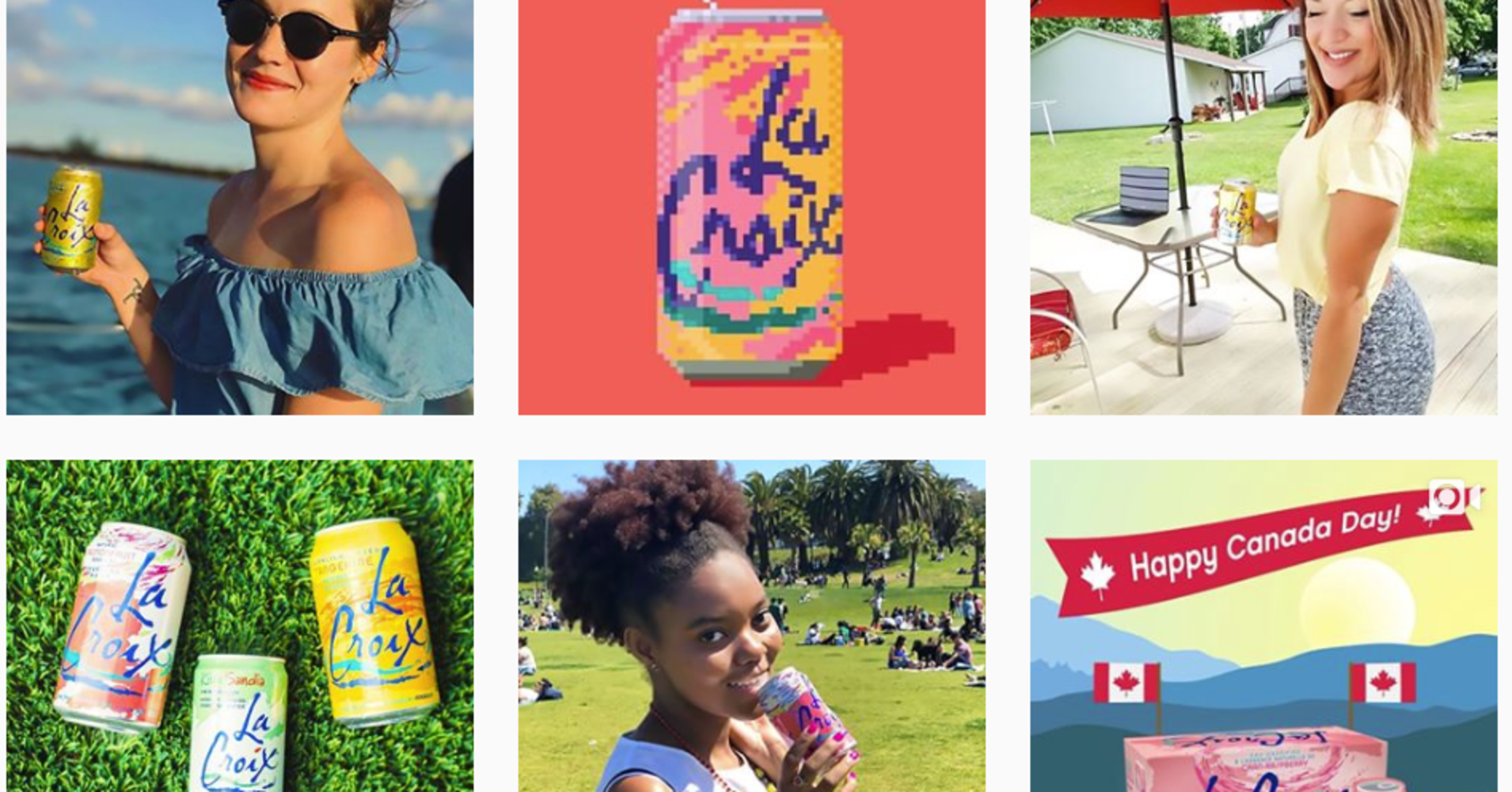

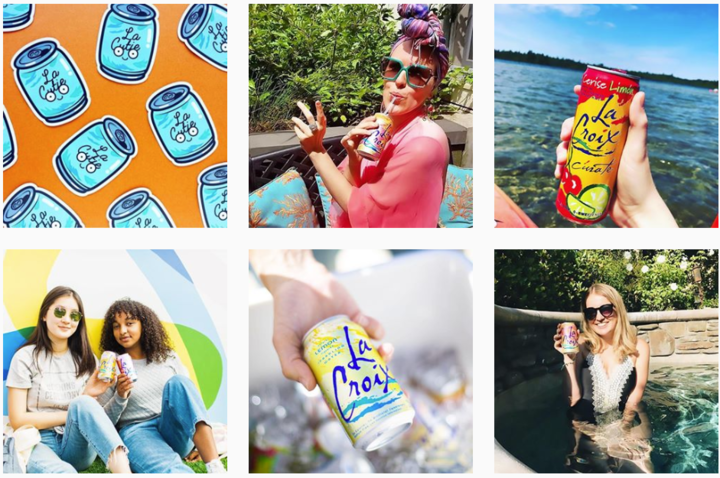

Instagram: lacroixwater

More than 1.9 billion liters of carbonated and flavored waters were sold in 2016, compared to 34.4 billion liters of bottled water, according to Euromonitor data. But the category is growing fast. From 2011 to 2016, carbonated water grew 70.4 percent by volume and flavored water grew 59.5 percent. Still water grew 29.9 percent, while sweetened beverages, like soda, declined 8 percent by volume.

“The impact really is that if consumers are moving in a direction, the big soft-drink companies want to make sure they’re offering options that have a good chance of capturing those consumers, as well,” Stanford said.

LaCroix is a convenient product for the growing population that’s cutting out sugar.

LaCroix was created by Wisconsin-based G. Heileman Brewing Company in 1981 and was acquired by National Beverage Corporation in 2002. The company owns several other juice, water and soft-drink brands, including Faygo, Mr. Pure and Everfresh juice.

LaCroix remained a relatively small regional Midwest brand until around 2011, when it saw some “meaningful movement,” and then had its jumping-off point around 2015, Stanford said.

“At some point, the brand managers did some consumer insights research that pointed them to some of the trends that we see on fire now and decided to use LaCroix as a brand to attack some of those trends,” he explained. “And, it turned out they were right, and they were pretty timely as well.”

The mainstream status of LaCroix is tied to the growing trend of consumers cutting back on sugar and looking for more natural products with fewer ingredients, according to Stanford.

Billing itself as calorie-free and sugar-free, and listing carbonated water and “natural flavor” as the only ingredients, LaCroix was able to position itself as a healthier option. The brand even partnered with the Whole30 diet. But, there has been much talk about what actually flavors LaCroix and what its true health effects are.

“When you start taking sugar out of drinks and you start looking for things without sugar, one of the ways to sort of make drinks pleasing is with bubbles and to make them refreshing,” Stanford said.

Younger consumers are driving the sparkling water growth, said Portalatin of The NPD Group.

“You have to think about the generation that is emerging into the dominant age cohort today,” he said. “It is one that grew up in elementary school without soft drinks and taught that sugary beverages are not good for you. So, there’s a whole different awareness today around health and beverages.”

Forty-eight percent of U.S. adults check product labels for sugar levels and list sugar as their top concern, and 53 percent report trying to reduce the amount of sugar in their diets, according to NPD research.

The flavored bottled water category grew 10.8 percent in volume in 2017, according to Beverage-Digest data. LaCroix was the fastest-growing brand in the category, leaping 52.6 percent by volume and grabbing an 11.8 percent share of the category in 2017, topping Perrier Flavors, which had a 2.3 percent share, and the Coke-owned Dasani Flavors, with a 1 percent share.

LaCroix masterfully built a following on Instagram.

Eric Pinckert, co-founder and managing director of BrandCulture, a Los Angeles-based brand strategy agency, told HuffPost via email that he refers to LaCroix a “gustatory click bait for millennials and Gen Z.”

“LaCroix cultivates an air of mystery by making sure nobody knows the secret recipe of ‘natural essence oils’ that flavor the seltzers,” he said. “The company adds sassy, visually arresting packaging and a relentless promotion of the drinks as a healthy alternative to sodas.”

The LaCroix mystique has helped the brand build a kind of cult following on social media, tapping into the “zeitgeist by stoking up a devoted fan base that advertises the product for the company — for free — across social media,” he said.

Instead of going the traditional, and costly, advertising route, LaCroix embraced social media micro-influencers to grow brand awareness in an authentic way. LaCroix also engaged with people who tagged the brand in Instagram posts, in some cases sending them vouchers for sodas.

“Our fans were highly engaged millennials, especially on Instagram, and I immediately recognized the need to engage with them as a brand and offer them a platform that will inspire them to use our products in many different ways and/or stages of life. This quickly turned our Instagram page into (our) most engaging platform and our fan base grew from 4,000 to 30,000 within eight months,” Alma Pantaloukas, LaCroix’s former social media coordinator and digital strategist, writes on LinkedIn.

Instagram: lacroixwater

LaCroix’s official Instagram page had 146,000 followers at press time.

“That a brand like that has a sort of grassroots mentality and really relies on consumers and social media to really embrace the brand as their own, it’s a case where the consumers drove the messaging for the brand,” Lyle Zimmerman, president and chief creative officer at Alchemy Brand Group, told HuffPost. Alchemy previously worked with LaCroix on its packaging design and has worked in package design and brand identity for several major beverage brands.

“A company like that really relies heavily on consumers to provide images of themselves enjoying the product. They rely on the consumers to drive the content. And I think that was a key difference,” Zimmerman said.

Social media conversations have revolved around how the brand’s name is pronounced, as well as flavor combinations and cocktail recipes using the beverage. The lack of traditional advertising gave the product an exclusive feel, industry experts say.

“Millennials certainly have been part of that drive, and the packaging appeals to them,” Beverage-Digest’s Stanford said. “The fact that it isn’t something that you’re going to see in a television commercial and that it’s something you might discover or your friends tell you about, that’s kind of fun. All of that just sort of adds to that whole vibe that millennials seem to gravitate toward.”

In addition to social media buzz, the number of Google searches including the phrase “La Croix” increased more than 760 percent from June 2014 to May 2018, when there were more than 350,000 searches, according to an analysis by marketing data provider SEMrush.

But LaCroix’s popularity has also brought controversy. National Beverage Corporation, owner of LaCroix, and its CEO Nick Caporella are facing questions from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission about some of its internal sales measurements, which Caporella has referenced in multiple news releases. The 82-year-old Caporella is also facing lawsuits alleging sexual harassment from two former pilots of a private jet owned by the CEO.

LaCroix’s popularity is forcing Big Soda — and everyone else — to innovate.

Beverage brands both large and small are now trying to capitalize on some of the same trends that brought LaCroix into the spotlight, Stanford said. Volume production of “megabrand” drinks like Coke and Pepsi, declined 2 percent and 4.5 percent, respectively, in 2017, according to Beverage-Digest data.

Stanford says a reason for this is the broad trend of Americans cutting out sugar, combined with an influx of new drink products.

“LaCroix absolutely will continue to grow,” he says. “But the competitive landscape’s definitely going to get more difficult, so they’re going to have to continue to be creative.”

The new competition from LaCroix is pushing the big soda brands to innovate and introduce new products, Zimmerman explained. PepsiCo recently launched its own flavored sparkling water brand Bubly, and Coca-Cola has been pushing its Dasani Sparkling brand and acquired sparkling mineral water Topo Chico in 2017, seemingly in an effort to compete with LaCroix.

“They can’t just sit back and crank out gallons of Coke the way they could in the past,” Zimmerman said. “Now, they’re being challenged to sort of re-create themselves, reintroduce themselves to the public.”

Pinckert agreed. “The big guys can’t help but look at the success of LaCroix and salivate,” he said. “When a brand captures the attention and engagement of consumers, it gins up the gears of innovation to take advantage of evolving consumer tastes.”

In its Q2 earnings call on July 10, PepsiCo said its sparkling brand Bubly is “off to a great start” and “continues to perform exceedingly well.” Going forward, the company said it plans to “continue to execute against the innovations in the newer categories,” including Bubly or its bottled still water brand LIFEWTR, to create growth in the business.

“When we looked at the sparkling water category, we saw an opportunity to innovate from within by building a new brand and product from the ground up to meet consumer needs,” Todd Kaplan, vice president, water portfolio, of PepsiCo North America Beverages, said in a news release when Bubly launched in February.

Even as the beverage industry becomes more crowded with new products, LaCroix still has plenty of room to grow, Stanford said.

“The question is the extent to which consumers start to move on to other things at some point,” he says. “It seems like sparkling water’s pretty well set and probably going to be around for a while.”